‘Here I am, not quite dying’

Peter Breedveld

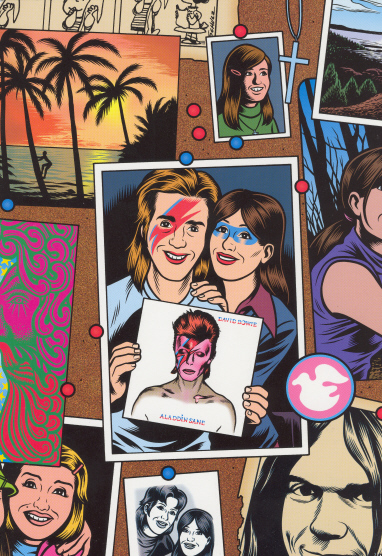

Illustration from Black Hole by Charles Burns

In 2013, when xenophobic racists in the Dutch media launched a meticulously coordinated attack against me in the form of vile accusations from many different sides, leading even to questions in the House of Parliament, I sat hidden in a small London hotel room. It felt safe there, it was like a warm womb. On television I saw a documentary on David Bowie, who had just launched a new album, The Next Day.

I bawled my eyes out.

On The Next Day Bowie sang ‘Here I am, not quite dying’. When I had dug myself out from the grave the racists had put me in, after wandering through London and subsequently through Tokyo for a few weeks, where I had encountered a green snake in a graveyard, who told me everything would be alright and that I needed to get my act together, that particular line felt like it was written for me especially.

My girlfriend felt the same way. “This song is about you”, she said. “This is what you are going to tell those motherfuckers.”

Weirdos

Bowie’s death has millions of people mourning, among them my ten year old son, who was just discovering the riches in his immense oeuvre (he texted me today: “Daddy, has David Bowie passed away?” followed by four crying smileys). Bowie is one of the biggest influences on Western culture of all time. But to me personally, and I know to many, many other people personally as well, people who have, at some point in their life, felt alienated or estranged, he showed the way through life’s jungle. Or rather, he had hewn out the path for us.

Bowie is the saint of the outsiders, the weirdos, the people who don’t fit in.

Bowie has saved my life on different occasions. In 2013, when I was convinced everybody was against me and I was worthless, evil even. When I just wanted to stop existing, driven to insanity by the racist vultures.

Bowie in drag

And years before that he saved my life when I was fifteen and so depressed I felt like there was a mountain on me, or that I was drowning in a wild sea. That there was no use fighting.

Bowie was the only person in the whole wide world who understood me. He was the man who made it acceptable for me, even cool, to be different.

I think I became aware of Bowie when I was about ten years old. I saw the video of ‘Boys keep swinging‘ on television. Bowie in drag, coming up on a catwalk as three different ladies, looking defiantly in the camera, then wiping off his lipstick and pulling off his wig while guitars were screaming like rabid banshees. It was the weirdest thing I had ever seen at the time. It was also the most liberating thing I had ever seen.

I grew up in conservative surroundings, even in the progressive seventies and eighties. I lived in a rural town, everybody was the same. You couldn’t be different. If you were different, you would best keep that concealed. Amsterdam was far, far away. Bowie taught me that if you are different, you better be different in an aggressive way. You better put your being different in everybody’s face.

And so I did. I was never going to be good at soccer, I was always going to be losing the fights boys picked with me, I was always going to be a weird kid, a geek, a boy who was seldom there, always dreaming, extremely, ridiculously shy. So I could as well celebrate my weirdness. Just as Bowie did. It even became an obsession for me to not be like the others.

Illustration from Black Hole by Charles Burns

Bowie Homo

The kids at school called me ‘Bowie Homo’ but I couldn’t care less. They were Neanderthals to me. They knew nothing, they were quite proud of knowing nothing. They were very intolerant of kids who knew things when the only thing worth knowing was soccer. ‘Gotta make way for the homo superior!’

I was quite alone in my admiration of Bowie until a new girl arrived who was into all those punk and new wave bands that followed the trail Bowie left through pop culture. With her I went to the concert Bowie gave in Rotterdam as part of his Serious Moonlight Tour. It was so amazing. It was my first time alone outside of my town, without my parents, with just this girl, and Bowie was omnipresent. He came from open windows everywhere, he looked at me from every corner, everybody seemed to revere him. It was like a religious experience, I felt part of a bigger whole for the first time in my life. I met people who were way, way weirder than me and totally unashamed of it.

The 25th of June, 1983, a sun-drenched day in Rotterdam; I had never been so happy before.

And it wasn’t just that. Bowie completely formed me as person. He taught me about George Orwell, Jacques Brel, Andy Warhol, Lou Reed and Lou Reed in his turn taught me about Delmore Schwarz. Bowie introduced me to Bertolt Brecht, Kurt Weill, Bauhaus, German Expressionism, the French magazine Harakiri, the comics of Mark Beyer, all those things I discovered through Bowie. Even my obsession with Japan began with Bowie.

Interview requests

I never met him in person, but I spent a lot of time of time chatting with him on his website, DavidBowie.com, as pioneering as everything else he has done. He was there virtually every night, posting messages on the Bowie message board under the moniker ‘Sailor’, making surprise appearances in the Bowie chat room.

We talked about comics, art, films, about silly stuff. He fooled around a lot. I even quarreled with him once about an interview he had done together with his wife Iman. I criticized him for having censored the draft article proposed by the interviewer, he got angry. “Do you know how many fucking interview requests I get?” he wrote to me, publicly. All the other fans jumped on me to rip me apart. The next day Bowie asked me, snarkily, but obviously feeling bad about it: “How does it feel to be famous, Peter?” and everybody cheered.

Still one of my most cherished memories.

Chopped liver

He would regularly butt in on conversations we as fans had with each other. We grew so accustomed to his presence that sometimes we would take him for granted. At one such occasion he asked me and the girl I was chatting with: “What am I, chopped liver?”

His website made it possible for fans to get as close to their idol as they ever could. It made it possible for him to hear the opinions of others than the people surrounding him, probably professionally agreeing with everything he said and did. He did not always like our opinions. But he kept uploading new stuff for us to judge. I remember him talking about us in an interview. “They are a cheeky bunch”, he said.

Then it stopped. I guess sometime around the early 2000s, which he called, if I remember correctly, ‘the Zeroes’, after a song of his. I think he also suggested the Naughties. After 9/11 the political discussions on his message board, and there were many, turned grim. There was a rift, especially between the hardliner American fans and the European lefties. Sailor didn’t turn up so often anymore and then the Bowie community started to disintegrate.

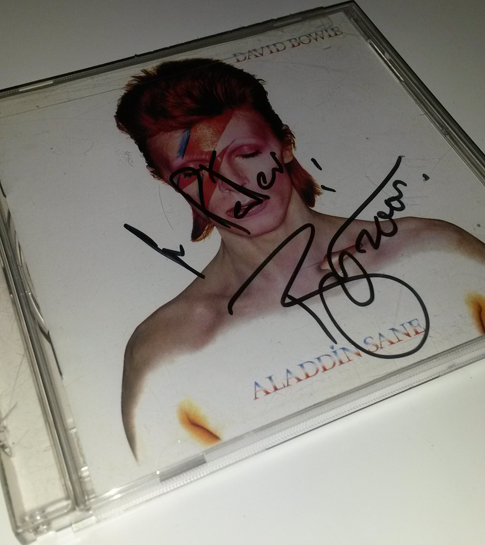

I still have all the cd’s Bowie had recorded until then, all signed by him and dedicated to me. ‘For Peter from David’. A present from him, to me. One of my most valuable possessions, you’ll understand.

Thank you Sailor, for everything. For making life goddamn beautiful. For giving us weirdos a home. For making us feel good about ourselves.

RSS

RSS